Normal Tolerance

A genetic counselor came to speak to our class yesterday about cystic fibrosis, and mentioned that a lot of the patients at Stanford have a “low illness tolerance” for birth defects and congenital or genetic disorders. The “clientele” are generally upper middle-class, well-educated, driven, hard-working couples that want the best for their children–as every parent does–but are seemingly more willing to terminate a pregnancy if there are any signs of possible problems. This brings up an array of interesting topics, and I’m especially fascinated by the Gattaca -like creepings and parallels. That a certain subset of the population would be genetically selecting out “less fit” children brings up a whole other set of questions. Is this just the next phase of evolution–the priveleged, intelligent elite now can create, on average, more genetically-elite children? Where does the testing end? Even if the latest “gay gene” discovery turns out to be less definitive than its discoverers predict, is that next on the list?

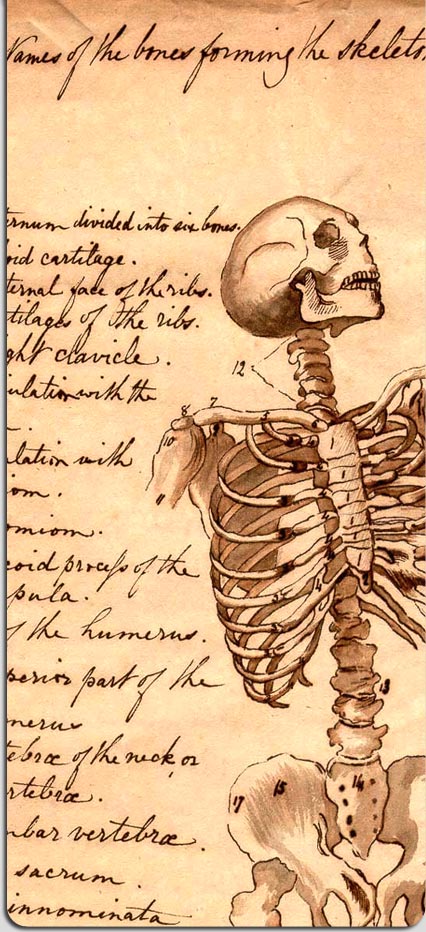

And so we stumble upon one of medicine and science’s greatest fears: that normal can’t be defined. Or quantified. Or pinned down. Pointed at. “There. That’s normal.” Sure, give me 10 people’s weights, I’ll calculate their mean value, the median, the mode, standard deviation–I could statistic the hell out of the numbers–and we’re nowhere closer to defining human normalcy. It comes up all the time in anatomy. Our cadaver has no obturator artery , but instead has a big side artery off his external iliac. Normal? Maybe not, but I doubt he ever knew the difference. After I asked if some arterial calcification was “normal,” my instructor reminded me that physicians are hesitant to ever use the word alone. It’s always quantified, “normal range,” or described as “common variation.”

“Duh,” you say. We’re all different. And unique and special. Joy to the world. But it’s more than that. It’s not just some superficial idea; it has consequences for how we define ourselves, how we view the world, how we practice medicine. The obesity epidemic has been a target of a great deal of media coverage and health discussion, but the main indicator, the body mass index , has been increasing across the population for the last century. It’s only now that it’s getting to the point where an excess of weight is causing health problems. Rewind to 1850, and a high BMI was probably considered extra-healthy. Cliched anecdote in point: if I had a nickel for every time my Nana squeezed my abdomen and said “we gotta fatten you up,” well, let’s just say I wouldn’t need to be on financial aid.

One of the most striking examples is the cochlear controversy in the deaf community . I first did some reading about the issue for a bioethics class in undergrad, and it’s hard for me not to see both sides of the issue. Basically, the argument goes like this: some in the deaf community see no problem with being deaf. There’s a culture, a language, and a community for the deaf, and some don’t feel like deaf people (especially children) should receive cochlear implants, which allow some people to become hearing. Doing so for all children means the end of the deaf community–like some sort of cultural genocide. And the other side argues that, yes, if the technology is available, people should be able to receive it.

It’s an even more controversial question when you apply the concept to homosexuality. If you could take a pill to turn straight, would you? If you could detect some sort of gay protein in the womb (it would, of course, fold like a rainbow, and be known in the literature as Fabulous ), would you terminate the pregnancy? It’s no easy question, and I think partially depends on a society’s tolerance, but it’d be an entirely different world without the contributions of gays. Many contributions probably wouldn’t have happened if the men and women in question had been born straight. So, even if it’s not considered normal, is it necessarily deleterious or detrimental? Or maybe we can use evolution itself as a barometer of normal. The argument goes that if homosexuals had no survival benefit for their kin (or more likely, siblings or siblings’ kin), it would have been bleached out of the human phenotype pool a long time ago.

There’s definitely an underlying assumption that any adversity in life (or abnormality) is inherently A Bad Thing. And while I’m not arguing that a person suffering from a tortuous, chronic disease is A Good Thing, my short term adversities have been the experiences that have led to my greatest long term gains. Or, better put by my mom, “Don’t worry, the dorks in high school always end up better, anyway.”