Or:

Why Lab Results And/Or Your Doctor Is Frustrating You

I find a good number of patients don’t really understand how doctors make decisions about diagnosis and treatment, so I thought I’d try to explain it all

out. Here we go.

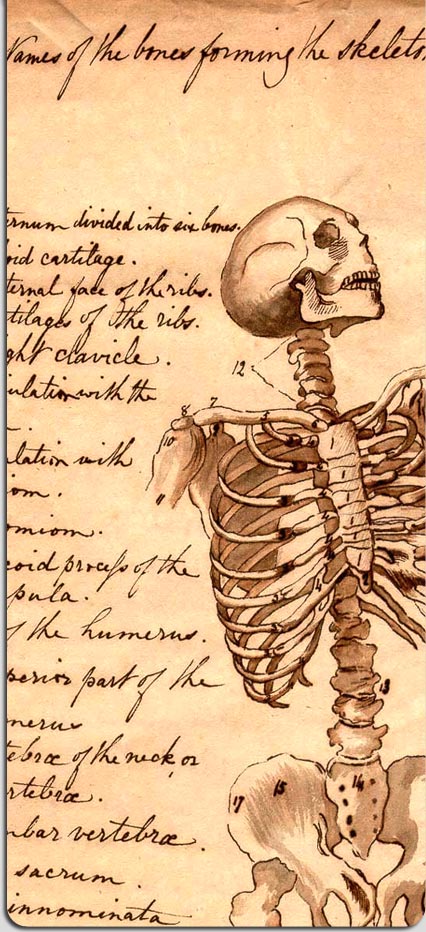

We’ll start with background knowledge and information. All the information that we learn before we start seeing patients as medical students is there to build a

foundation to try to guide our thinking. For example, we take anatomy to understand the body and the relationship of everything to everything else, so that we can

start to think about what might be causing someone’s problem. (For example, if you have pain in your abdomen just below the lower ribs on your right side

— we call that the “right upper quadrant” or “RUQ” — it leads us to think of things in that area that might be hurting. Not just

your liver or gall bladder, but sometimes pneumonias in the bottom of the right lung, the stomach, or the small intestine.) Sometimes the body can trick us, so we

have to make sure we aren’t guided solely by anatomy, but it gives us a place to start. (This trickiness is called “referred pain;” if your

diaphragm hurts, it can actually cause shoulder pain; if your gall bladder hurts, it can actually cause shoulder blade pain. Curse you, confusing body!)

And that’s just anatomy. We learn physiology, which tells us the rules the body follows to keep itself alive; pathophysiology, which tells us what happens when

the body messes up, but still tries to apply those body rules; pharmacology, which tells us how drugs work on cells and organs in our bodies, which drugs to use to

treat certain diseases, and the predicted side effects of those drugs.

Like I said, this is all just foundation. As we say, “Patients don’t read the textbooks,” meaning that when someone comes in with a certain type of

problem, they don’t always show the same symptoms or problems we learned about initially. Guidance but not absolute prediction. (The “classic”

picture of someone having a heart attack is severe chest pressure, clutching their chest with their arm. But very often, people don’t have chest

pressure–they may just feel weak, or have difficulty breathing.)

Now one of the hardest parts of medical school is inverting your knowledge. See, when we learn in the classroom for the first two years of school, it’s learning

about

diseases

. But you patients don’t come to us with diseases, you come to us with

symptoms

. And the damned thing about

symptoms

is that there’s any number of body systems or diseases or problems that can cause your symptom. Only

very rarely

does one single symptom let a doctor immediately know the disease. (And of course we have to know the disease accurately to know the treatment, because some

treatments can make certain diseases worse if we’re wrong.)

Here’s an example. Let’s take difficulty breathing, or “shortness of breath” or “SOB” as we call it. Here’s a very short

list of the causes, based on body system (the real list is much much longer):

- Vascular Causes: Aortic Dissection

- Infection: Pneumonia

- Neoplasm: Lung Cancer

- Drugs: Amiodarone-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Idiopathic Causes: Sarcoidosis

- Congenital Causes: Heart Defect

- Autoimmune Causes: Lupus

- Trauma Causes: Pneumothorax; Toxin Causes: Aspirin Ingestion

- Endocrine/Metabolic Causes: Diabetes (Diabetic Ketoacidosis)

… and so on. So when you see a doctor for a certain problem you’re having, we try to tease together parts of your story, and add in your other symptoms,

what we know about your other medical problems, what medications you’re taking, your age, your life, and your risk factors for certain diseases to come up with

a list of things that we think it might be. It’s all educated guesses. This list that we put together is called a “differential diagnosis,” and

it’s ranked in order of likelihood. The minute you start talking to your doctor, he or she has started putting together a differential diagnosis. And as you say

certain things, or answer certain questions, that differential can immediately change. Heart attack can go from top of the list to somewhere near the bottom, with

heart burn replacing it at the top.

By this point, just with talking to a patient and examining him or her, many common diseases can often be diagnosed, based just on this information. But our top guess

on our “differential” isn’t always right. So even if we’re pretty sure it’s, say, hepatitis, it still could be other things. (This is

all going on inside our heads while we’re talking to you, hence us sometimes seeming like we’re zoning out or not listening to you.)

Since we believe in “Above all do no harm,” and we generally try to only do things (give medications, recommend procedures or surgeries) if we believe

that the benefits outweigh the risks (

everything

has a risk and a benefit, including seemingly harmless over-the-counter medications), sometimes we need a test to let us confirm that our diagnosis is correct. If you

have a classic story and exam pointing toward strep throat, the doctor may just go ahead and prescribe antibiotics. But if the story isn’t exactly right, or the

timing is off, or your throat doesn’t totally look like strep, the doctor may order a strep test to confirm that he or she is right.

And that’s just the beginning. (To be continued…)

Comments Off

on How Doctoring Works